"The Big Stick" An Exclusive Tour of the USS Iowa Battleship

Modern warfare as we know it today is coined asymmetrical. We utilize terms like surgical, tactical, over the horizon targeting, standoff weaponry, stealth mission, or fire and forget. In today’s combat environment of asymmetrical warfare, the United States will utilize a multibillion dollar aircraft carrier from a seven ship task force to launch a two hundred million dollar aircraft. This aircraft will fly 500 miles to launch a half million dollar missile. After launch, this missile will fly over 2500 miles per hour from 50 thousand feet of altitude to “take out” an enemy combatant who has pinned down a single fire team or squad of US soldiers or marines with what’s known as a “technical”, AKA a $500 truck with a Vietnam era Russian machine gun mounted in the bed. The force ratio is baffling and mind boggling. It didn’t use to be this way. Not in the slightest bit.

Four special ships were built in the time of global war. Having fought and survived the perils of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans during World War Two, the four ships would go on to participate in conflicts all the way until the end of Operation Desert Storm in 1991. Their service record is unparalleled. No other warships have actively fought for fifty years. The four ships are called the Iowa, the Wisconsin, the New Jersey, and the Missouri. Collectively, they were designated the Iowa class. A new breed of battleships, they were designed to fight and survive during the coming of age for aircraft carriers. The Iowa class battleships were the fastest battleships ever designed. Speed was paramount. Despite growing over two hundred feet in overall length and displacing ten thousand tons more than their preceding class, the Iowa class ships were able to cruise over ten km/h faster reaching speeds of 65 km/h making them the fastest battleships ever built. Ships during this period more than any other equipment were designed with redundancy upon redundancy. Without computerized control, each machination of the bristling battleships was controlled from mechanical actuations. The vessels had armor upon armor, fire control for fire control, and controls well past the tertiary fallback. The Iowa class battleships were and still are arguably the hardest to sink ships of war ever made.

Photo provided by Dave Way

Because of the Iowa class battleships longevity of service, the ships were continuously updated to maintain their effectiveness as flagships of the United States Navy. At the time of their development in 1938, nuclear fission was still a theoretical concept yet to be tested (only two German scientists held the ideas in their minds) and instant coffee wouldn’t be invented for another year. By the time the battleships were finally released from service in 2006, Facebook was available and GPS guided missiles were commonplace on the battlefield. It is difficult to think of another vehicle or piece of technology capable of maintaining dominance in its field for almost 70 years. The Iowa class battleships were built to last and a living example of life at the time of their creation.

After completing their service in 2006, the four Iowa class battleships were slated to become museum ships. The USS Missouri resides now in Hawaii. The USS New Jersey is in the Delaware River in Camden, NJ. The USS Wisconsin is docked in the ship filled waters of Norfolk, Virginia. Lastly, the USS Iowa overlooks the bustling port of Long Beach and San Pedro, California. All four ships are being restored by dedicated volunteers and a few paid staff. While maintenance occurs, simultaneously the ships are open to the public and wide eyed families, nostalgic veterans, and history enthusiasts are able to take in the powerful experience of walking through and touching a weapon of war we have been fortunate enough to not experience again.

At the end of July, Blacktop Ranger was granted unrivaled access to the USS Iowa’s storied compartments. I invited a good friend of mine, Evan Glodell of Coatwolf Productions to join me for the experience. Evan and his team at Coatwolf are not just award winning filmmakers but more importantly, are mild evil geniuses of technology and machining. Their films utilize handmade machines that shoot fire or emanate music with lightning generated from midcentury transformers and conductors. The characters in the films use homemade flamethrowers and carry man portable machine guns with carrying rigs made of steel attached to their bodies. I could think of nobody more capable of appreciating the complicated but beautiful composition of these pre-computer steel behemoths.

In a Blacktop Ranger approved stroke of luck, Evan and I arrived at the Iowa greeted by a gathering of Ferraris. A car show at a battleship. What more could you ask for in life! Guiding us through the maze of compartments would be Dave Way, the head historian for the USS Iowa Museum. Dave is a full time employee with his office deep in the bowels of the slumbering giant. We met Dave around 11 AM on the pier along the ship. His smile was immediately infectious and I knew we were in for a fantastic time. As we walked the long walk up the gangplank, Dave and I hashed out the plan for the exclusive tour. We would begin with an abbreviated walkthrough of the “regular” tour available to the public and dive into the bowels of the beast when specific areas were nearby. While I have visited the Iowa repeatedly, Evan had yet to experience the ship so we wanted him to see as much as possible.

We began our tour from the stern of the ship, immediately seeing a Piasecki HUP2 “Retriever” helicopter. The HUP 2 was an upengined version of the original HUP, which was designed in 1945 and was one of the first helicopters utilized by the US Navy. While the feat was unintentional, the HUP was the first helicopter ever to perform a successful loop. The aptly named Retriever was utilized by the Iowa for search and rescue of overboard sailors or fellow servicemen, as well as target spotting during combat. The Iowa was capable of receiving and launching any helicopter utilized by the US Navy off the fantail helipad and was one of the first ships to have a helicopter pad on its decks.

One of the first compartments Dave led us into was already off the regular tour path. Not that I was complaining. As we ducked through the reinforced bulkheads, we were introduced to one of the radio rooms of the ship. Wall to wall radios lined the compartment. Utilized during her service to transmit messages, the area is now frequented by authorized HAM radio enthusiasts, who restore and use the equipment on a regular basis. One of the first long distance encrypted radios sits within this compartment, as well. Used for broadcasting confidential orders, the machine is painted in the same color as the White House-Kremlin hotline phone.

From the radio room, we navigated onwards to another ‘restricted’ region of the ship. The Combat Engagement Center (CEC). Different from the ubiquitous Combat Information Center on most ships (the Iowas have a CIC as well), the CEC was an uparmored compartment close to the bridge so the command staff had access to eyes on combat information without having to run deep into the bowels of the massive vessel. Because of the major updates to the ship in 1984, the Iowa’s CEC contains modernized radar screens and the tomahawk and harpoon missile launch controls along with the anti-missile defense system controls. The displays and monitors contrast heavily with the 1940s technology seen in the other compartments.

Two of twenty 5 inch guns on the USS Iowa

main 5 Inch gun on a modern US Navy Arleigh Burke Class destroyer

Having left the dark green lit CEC, Dave took Evan and I back outside onto the port side main deck, where we were shown to one of ten dual five inch gun turrets. The measurement of naval guns goes by internal diameter of the gun or cannon’s bore. So a five inch shell is five inches in diameter. The dual five inch gun turrets were dual-purpose weapons firing a 55 pound (22kg) shell up to a range of ten miles. The dual purpose turrets allowed for 85 degrees of inclination making them capable anti-aircraft defense as well as traditional ship to ship or ship to land weapons. Each five inch turret crew was capable of loading and firing up to 30 rounds a minute between the two guns. The fives were ubiquitous to the United States Navy being used on nearly every ship from destroyers to carriers. While a modernized single five inch gun is used as the main kinetic armament on most modern US naval warships, the 20 five inch guns housed in ten turrets were only the secondary armament on the Iowa. Only mass produced destroyers like the famous Fletcher class were equipped with 5 inch mounts as their main armament during World War Two.

USS Wisconsin firing her 16” main guns for the final time

While the five inch guns are impressive, the Iowa’s main weapons were legendary. Each Iowa class battleship were equipped with nine 16 inch main guns fitted in three truly massive turrets. The “three-gun turrets" were capable of firing each weapon at individual points of aim allowing for nine different trajectories to be plotted and fired at once. The turrets in total weighed over 2000 tons and required 79 men each to operate. The turrets extend deep into the ship going four whole decks down beneath the barrels. The Iowa class battleship’s 16"/50 caliber Mark 7 – United States Naval Gun were the largest naval weapons ever fielded by the United States. When a full broadside was fired (all nine at once) the ship became roughly 15 tons lighter. In total, the Iowa class battleships carried over 1100 rounds for their main guns alone. Each shell weighed somewhere between 1700 and 2700 pounds (770 to 1225 kg) and required six individual 100 pound (45 kg) bags of gun powder pellets to fire. The maximum range of these massive shells were around 24 miles (39 km) and the air time from initial firing to impact could last as much as a minute and a half. After World War Two development of atomic technology lead to the creation of a nuclear shell designed for the 16 inch guns. If fired, each shell would have produced a blast equivalent to the Hiroshima bomb.

From the 5 inch mount, Dave exuberantly led us up the endless staircases to the bridge of the Iowa. Because of the critical nature of the crew located on the bridge, the Iowas were designed with multiple areas for commanding and steering the nearly 900 foot (275 m) long vessel. Each location has a different threat protection. When the coasts were clear so to speak, the helmsman and Captain could control the vessel from a pleasant flying bridge with a view unrivaled by the nicest of yachts. If they were in inclement weather, the crew would utilize the regular navigation bridge with traditional controls. Should combat be imminent however, the essential command crew would fall back to a citadel of steel going from level 3 to level 5. Within this steel bunker, the Iowa’s command staff would fight from behind 17 inches of reinforced steel. Each door to these conning towers weighed 2000 pounds alone. Like children at a McDonald’s playground, Evan and I immediately ducked down to get through the small tunnel-like doors.

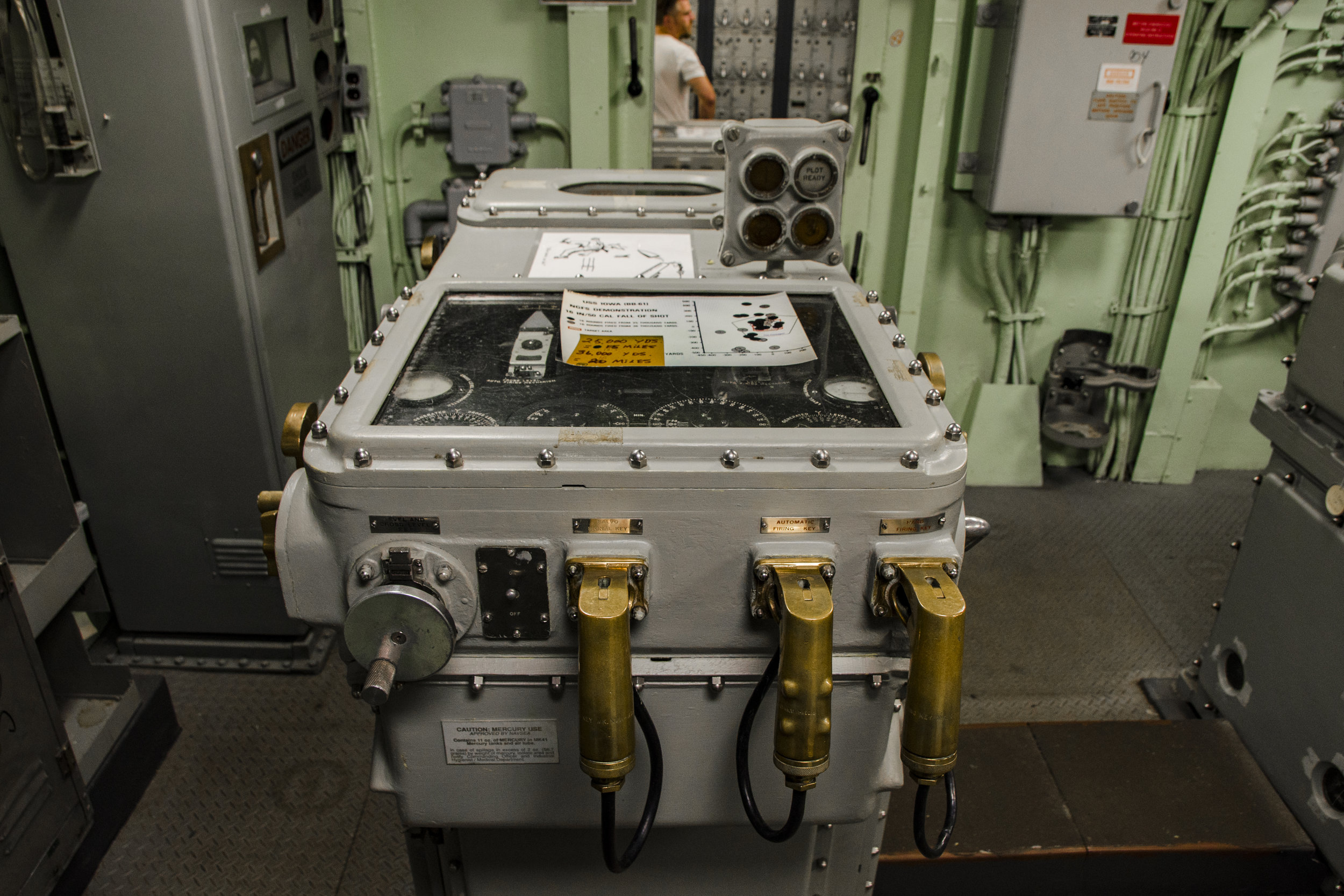

Having had a brief moment of fresh air atop the flying bridge, we dove back down into the depths of the ship to finally go to the compartment I was most excited for, the main battery plotting compartment. Arguably the most important thing to a battleship. From within this compartment the main and secondary weapons were aimed and fired. From the moment we ducked under the reinforced bulkhead, we were astounded by the mechanical complexity before us. There were wall to wall analog controls in multiple rooms. I attempted to count the total number of rotating 8” controls and surrendered at 400. The highly trained targeting crews working together made the Iowa class ships the pinnacle of accuracy during the Second World War and the equipment functioned so well, none of the ships were updated to GPS or computer controlled targeting systems. The jewel of the system is known as a Mark 8 mechanical-analog computing range keeper. The Mark 8 is a box roughly 3 feet wide and table height that physically computed the necessary positions for the main guns. Toggling the inputs to generate a solution was one of the highlights of the tour. Each input ticked or resonated beautifully like a Rolex watch of precise death. Just a few feet away on another analog mechanism was the behemoth guns’ triggers. Sadly, there were no flashing red buttons labeled “DOOM”. 3 polished brass handles with black enamel triggers were deemed sufficient. I’d have gone with DOOM buttons myself, but oh well. Don’t worry, we of course pulled all the triggers. They emanated a soft click. I can only imagine the roaring vibrations, which would have followed.

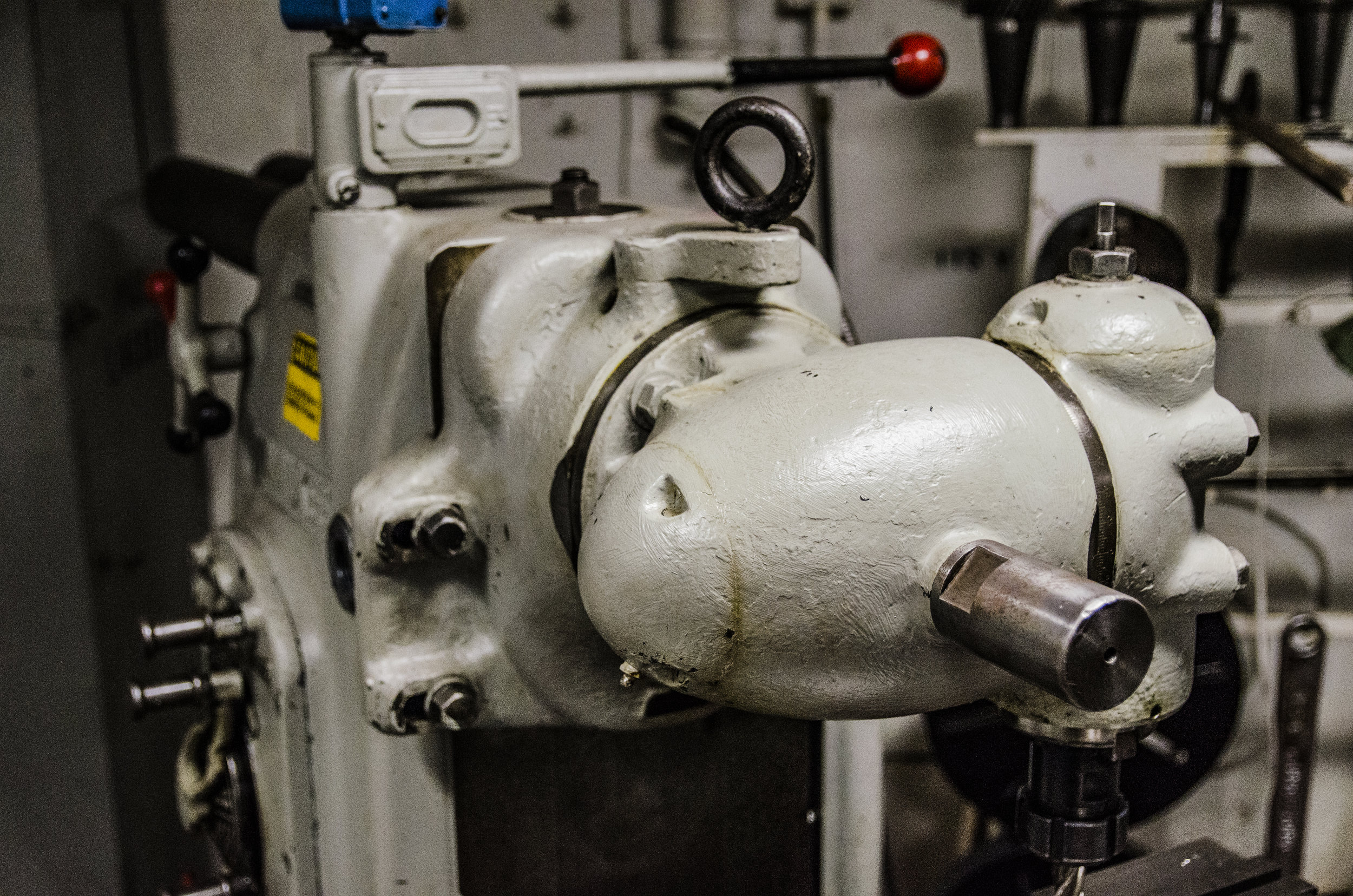

Having had our fill inside Dr. Evil’s playhouse, the three of us joked our way into one of the prettiest sights I’ve ever seen, the machine shop. If your dad is a vehicle enthusiast or your father or grandfather was a machinist when you were young, I assume you’ve heard them lament over how tools aren’t like they used to be. It’s ok. I didn’t understand why they did it either. Then I grew up and visited a harbor freight. Too broke to afford the good stuff, I purchased what I could afford and was proud to open my rough grey tool box. Then I lamented when my 50 cent ratchet wouldn’t get a good grip. Then and only then I understood why people look at the older equipment like it’s liquid lust. It’s because the old tools just plain worked. No plastics and no sacrifices. Iron and steel casings with heavy duty metal gears or double insulated wiring. The older tools last forever and you know when you sink the socket around a nut or line up the saw to the wood… it’s going to work and it’s going to do it well.

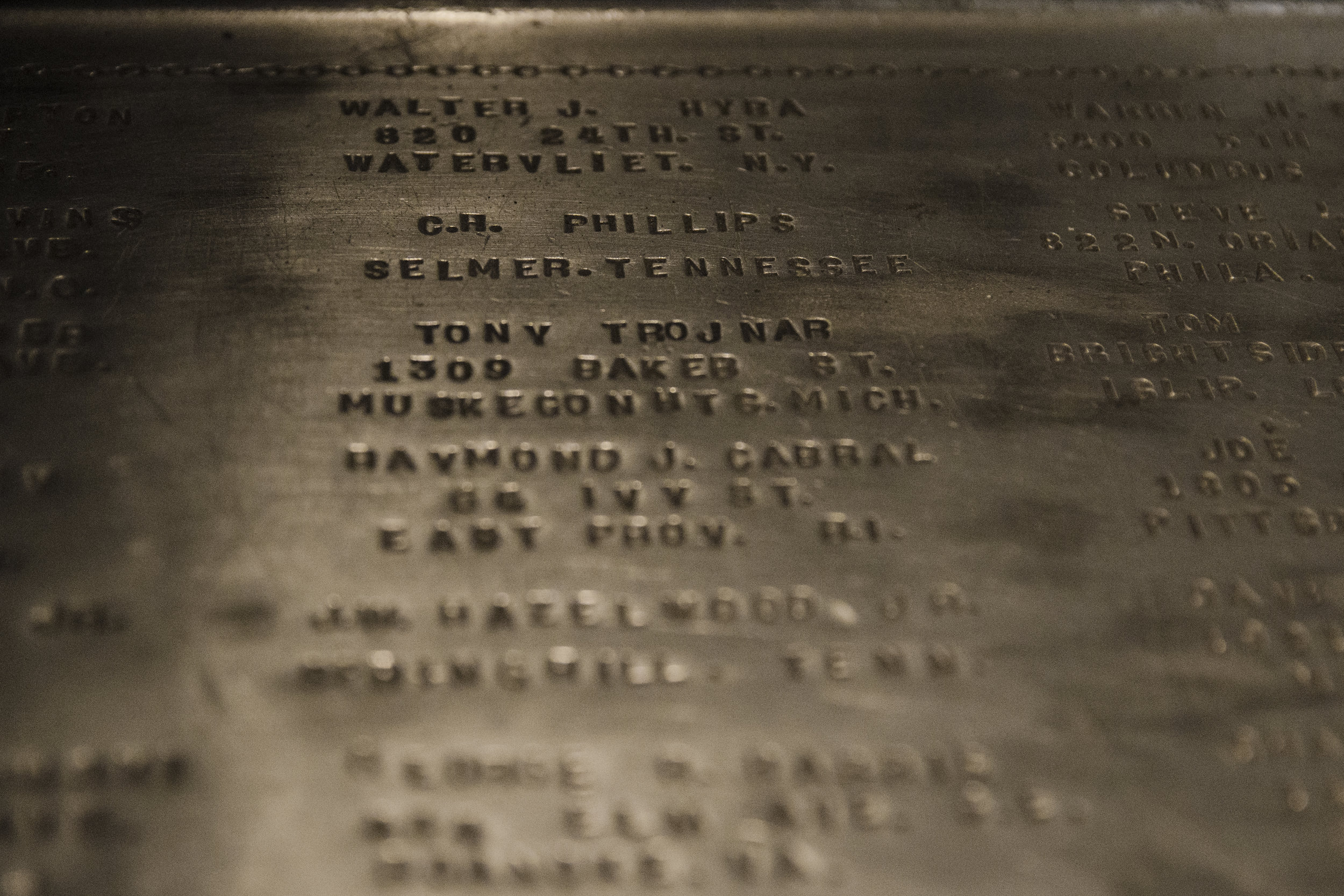

With that in mind, imagine Evan’s and my pleasure when we entered an absolutely massive repair shop filled with machines built in 1939. Every tool you could possibly need to maintain and repair a warship the height of the empire state building was present. The whole workshop had a hanging monorail on the roof to allow heavy equipment or workpieces to glide down the rails smoothly to wherever it needed to go. On one of the workbenches, Dave showed us something that really reminded me the gravity of where I was standing. As an enthusiast of old school equipment it’s very easy to forget the initial purpose of the monster I was walking through. I had become lost in the millions of switches and levers and valves and forgot I was on a vessel, which was shot at and fired back even harder. People fought and died on this warship to stop the evil, which darkened the 20th century. On that non-descript workbench in the corner, we saw the names of everyone who served in the compartment on the day World War Two ended. Their names, date of birth, and even their home address were etched beautifully into the polished steel workspace. Imagine the elation of these American sailors as they wrote their names into a tiny corner of history knowing they had bled for the world and that it was finally over.

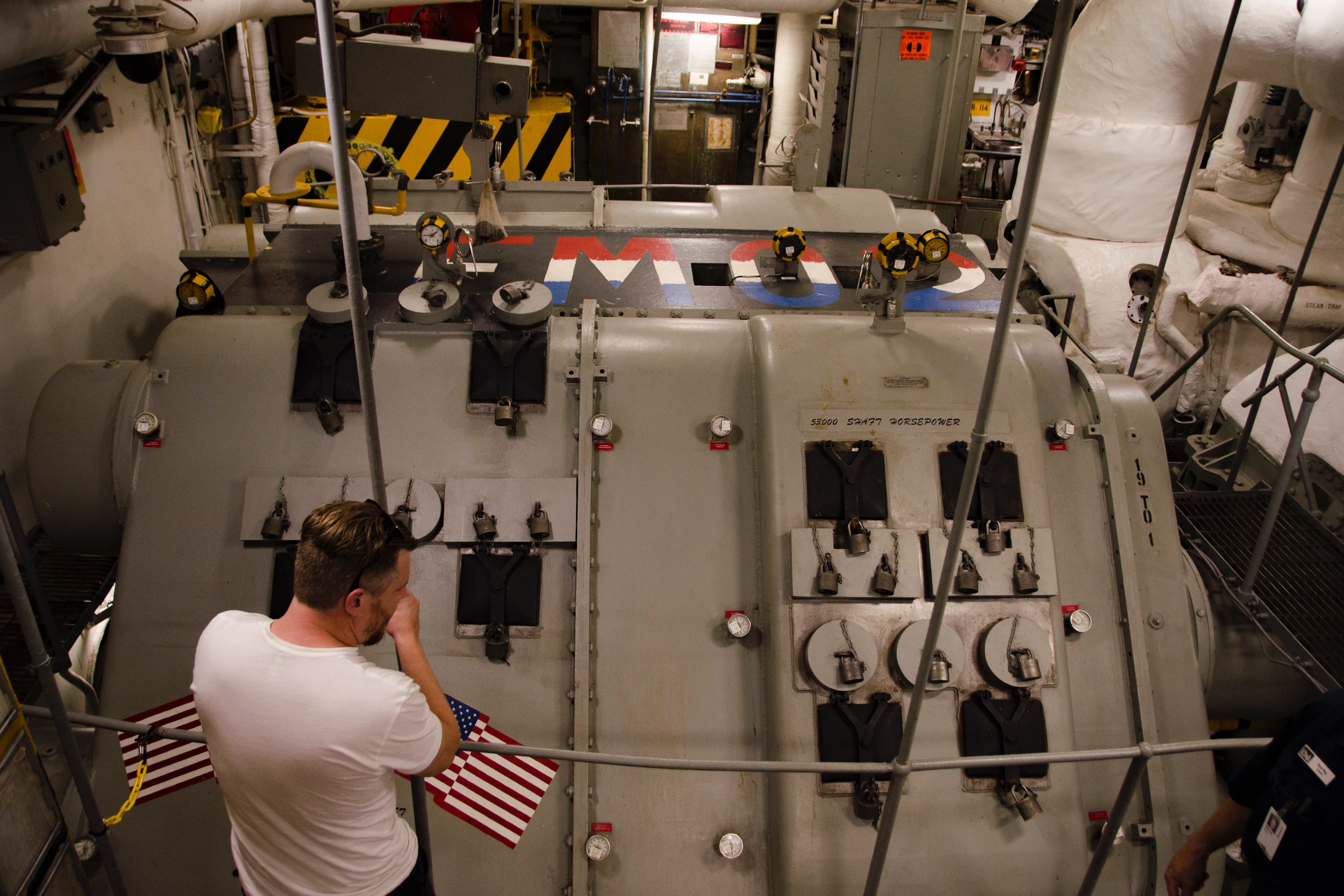

A bit humbled, we left the workspace following the monorail which snaked its way to something called “Broadway”. Unlike a civilian ship which is “easy” to navigate, a warship is designed to survive first and as a result the ship feels like a massive steel maze. Have you ever been playing a video game and can’t find the last checkpoint to leave an area? Walking through the Iowa feels just like that, only you're drunk and can’t remember where you’ve already been. Broadway is an aptly named corridor on deck 3 of the ship that is one of the few straight through walkways below deck. The 256 foot (78 m) long corridor runs down the center of the ship and connects the four fire rooms with the four engine rooms. As Dave explained, “Iowa’s propulsion system begins at the start of Broadway with Fire Room Number 1, followed by Engine Room 1. The remaining 2, 3, and 4 Rooms follow this same order.” To propel the Iowa class at a consistent speed of 33 knots, the ship’s propulsion systems are unbelievably large. The Iowa class utilized eight humongous 600 psi boilers to generate the steam for the turbine engines farther behind. Each boiler spans three decks from top to bottom and when running at full power, would consume ten thousand gallons of fuel per hour. One of the most intriguing things about the massive boiler rooms was the simple and low tech solution utilized to verify smooth operation. Just as a mechanic would look at the exhaust to check the amount and color of smoke leaving the pipes, a boiler engineer would utilize a periscope to visibly check the smoke coming from the stack above.

From the boiler compartments, the steam generated snakes its way into equally large engine rooms. The eight boilers provided steam for the four engine rooms. Each engine room consists of a high and low pressure turbine that are paired with an individual propeller. When working at full tilt, the 8 boilers fed the 4 turbine engine systems enough steam to generate 212,000 shp (shaft horsepower). To relate the ridiculous scale of the boilers, consider the largest steam locomotives utilized in the United States, the Union Pacific Big Boys. The Big Boys were built at roughly the same time period from 1941 to 1944. The locomotives weighed 381 tons, were 132 feet (40 m) long and generated 6,290 hp. That means to generate the same amount of power as the Iowa, it would take 338 Big Boys in tandem. On rails, the trains would span over 8 miles (12.9 km) long.

A battleship would not be a battleship without armor. The armor on these unrestricted weapons of war is unparalleled today. In the modern Navy, defense is a deadly game of interdiction. Missiles are to be intercepted by jets, then ship born counter missiles and close in radar controlled guns as a last ditch effort. During the unconditional warfare of World War Two, defense was catching the VW Beetle weighing projectile with your teeth, spitting it out, laughing and then firing nine monstrous shells back with vengeance. The Iowa was designed to protect itself against its own weaponry. Her triple bottom hull was well designed against torpedoes and the massively thick sloped sides known in warship parlance as the belt were a foot (30.5 cm) thick. The main guns were housed in turrets that ranged from 9.5 inches to 19 inches (24.1 to 48.3 cm). And just in case an enemy was able to plant a bomb, torpedo, or shell in just the right place to penetrate the interior decks, there were another 1.5 to 6 inches (4.5 to 15.2 cm) thick with bulkheads ranging from 11.5 to 14 inches (29.2 to 35.6 cm) thick.

Despite being 70 years old, there is still a large camp that wants the Iowa class battleships back in action. Today’s Navy fights with missiles launched from aluminium hulled ships with only Kevlar to protect crews in vital areas. Many individuals believe the monstrous steel warships would be unsinkable when paired with the US’s nuclear carrier ranged defenses. Many proposals have come and gone to turn theIowas into ultra-lethal anti-missile defense ships while still retaining some of their main guns to obliterate any warship that comes nearby. No current naval vessel in the US fleet is equipped with a gun larger than the Iowas’ secondaries. A 16 inch shell is a guaranteed to annihilate any modern naval vessel afloat with a single barrage. Unlike missiles which can be intercepted, the big gun shells are unstoppable in flight.

Sadly, the Iowas were deemed too expensive for continued operation and now reside as monuments to a time gone by. Walking through her hallowed corridors was an absolute honor. Compared to today, where all the action of devices is behind plastic and tucked away, being able to see, feel and even smell extremely well made devices with layers of redundancies was absolute sensation candy. While we may have made things more efficient in the 21st century, the USS Iowa and her sister ships are a reminder that just because something is older doesn’t mean it cannot work just as well if not better when it is built to last.

GALLERY